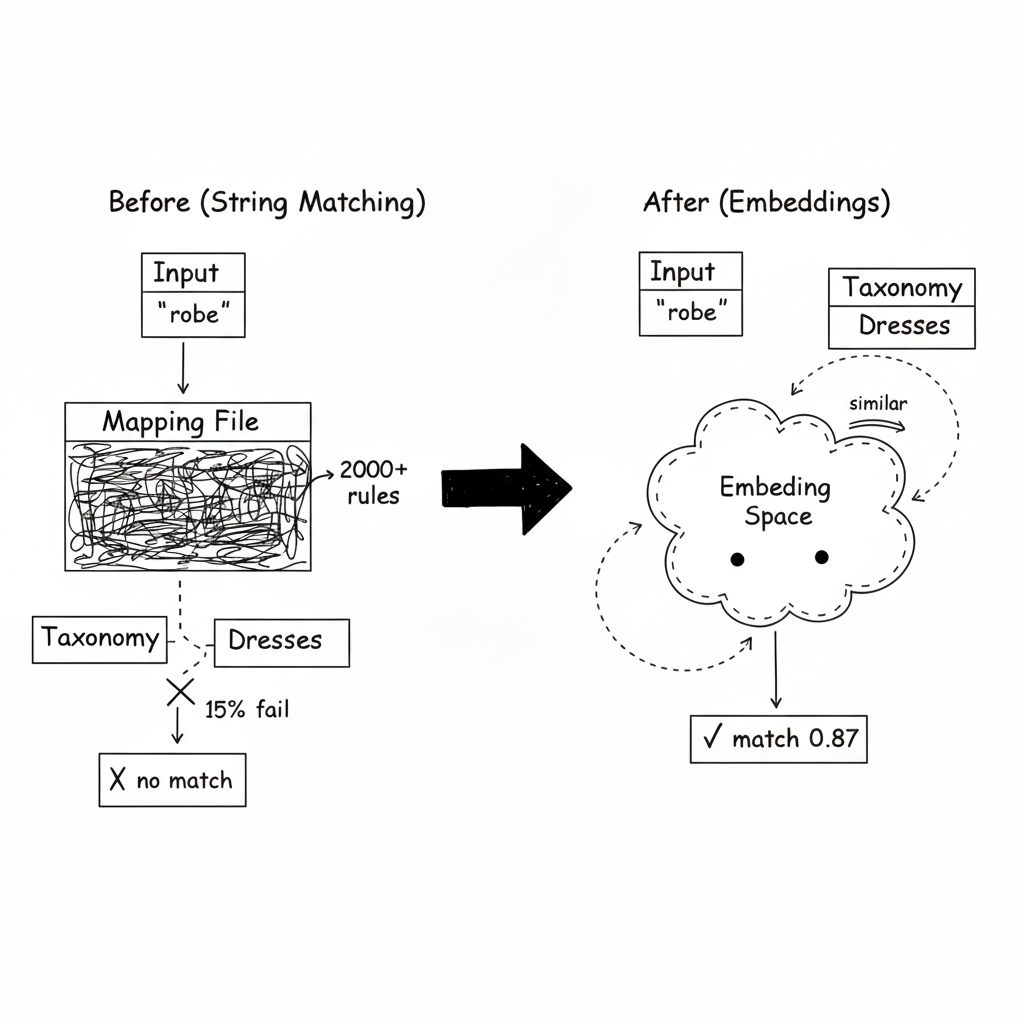

I was staring at a 2,000-line mapping file, and I knew it was a losing battle.

The file was supposed to translate incoming product labels into our internal taxonomy. "T-shirt" to "Tops > T-Shirts." "Jeans" to "Bottoms > Pants > Jeans." Simple enough.

But then the French supplier started sending "pantalon." And the UK partner used "trousers." And someone else sent "joggers"--which could be athletic wear or casual pants depending on context. The mapping file grew. The edge cases multiplied. Every week I was adding new entries, and the failure rate stayed stubbornly at 15%.

One afternoon, I added the 47th variation of "dress" to the mapping file. Robe. Frock. Gown. Vestido. Kleid. I stepped back and thought: there has to be a better way.

The Obvious Approach (And Its Limits)

String matching was the first attempt. If the input contains "dress," map it to "Dresses." If it contains "pants," map to "Pants."

This worked for the easy cases. It failed on everything else: French terms, shortened forms, and context-dependent words.

So I added aliases. Then regex patterns. Then language-specific lookup tables. The mapping file became a monster--and it still failed 15% of the time because there was always some new variation I hadn't seen before.

The Realization

I was debugging a misclassification one day--something labeled "robe longue" had been classified as "Unknown"--when I noticed something in my embedding logs.

I'd been using embeddings for search, and I'd run the input text through the same embedding model just to log it. On a whim, I pulled the embedding for "robe longue" and compared it to the embedding for "dress."

Cosine similarity: 0.87.

I sat there for a minute. The embedding model knew these meant the same thing. It had learned, from millions of text examples, that "robe" and "dress" appeared in similar contexts. It didn't need a mapping file.

"I don't need to enumerate every possible input. I need to teach my taxonomy to speak the same language as the inputs."

The Trick: Embed Your Taxonomy

Here's what I built:

Instead of matching strings, I converted both sides--the input AND the taxonomy--into the same embedding space. Then classification became similarity search.

Step 1: Expand each taxonomy node into a rich text blob with synonyms, translations, and common variations.

Step 2: Pre-compute embeddings for each taxonomy node at startup.

Step 3: When an input arrives, embed it and find the closest taxonomy node using cosine similarity.

Now "robe longue" finds "Dresses" because their embeddings are close--even though they share no common strings.

What Surprised Me

The model already knew multiple languages. I didn't need separate French and English mapping files. Modern embedding models are trained on multilingual data. "Robe," "dress," "vestido," and "kleid" all cluster together naturally. One taxonomy, all languages.

Hierarchy came for free. If something matched "Pants > Jeans" with high confidence, it implicitly matched "Pants" too. I added explicit hierarchy propagation--a match at a leaf node boosts the ancestors--but the core insight was already there in the embeddings.

Some categories needed higher thresholds than others. A cosine similarity of 0.7 means different things depending on the category. Matching a broad category like "Clothing" is easy--lots of things are clothing. Matching a specific category like "Slim Fit Jeans" requires higher confidence because there are so many similar alternatives.

I ended up with depth-aware thresholds: top level categories use 0.55, mid level uses 0.65, and leaf level uses 0.75. Deeper categories need more confidence to match.

The Production Details

Pre-compute everything. Embedding the taxonomy nodes at startup takes a few seconds. Caching input embeddings avoids re-embedding the same text repeatedly.

Handle confusing pairs explicitly. Some categories are semantically close but should be distinct. "Costumes" and "Dresses" overlap in embedding space--they're both garments people wear. I added negative examples to push them apart.

Build a feedback loop. When a human corrects a classification, I add the misclassified term to the correct category's expansion text. The taxonomy gets smarter over time.

Version your embeddings. If you change embedding models, all your taxonomy embeddings need regeneration. Track which model version created which embeddings.

When NOT to Use This

- Structured input already exists. If data arrives with category IDs, just map them directly.

- Exact match is required. Semantic similarity is fuzzy. For legal or compliance reasons, you might need human review.

- Taxonomy changes constantly. Re-embedding the whole taxonomy is expensive. This works best when the taxonomy is stable.

- Sparse taxonomy nodes. Single-word categories like "Other" or "Miscellaneous" don't produce meaningful embeddings.

The Takeaway

I spent weeks maintaining a 2,000-line mapping file that still failed 15% of the time. The string-matching approach was doomed because I was trying to enumerate an infinite space of possible inputs.

The embedding approach flipped the problem. Instead of listing every input variation, I taught the taxonomy to understand meaning. The model had already learned that "robe" and "dress" were related--I just needed to ask the right question.

The mapping file is gone now. The failure rate dropped to under 2%. And when someone sends a new language variant I've never seen before, it usually just works.