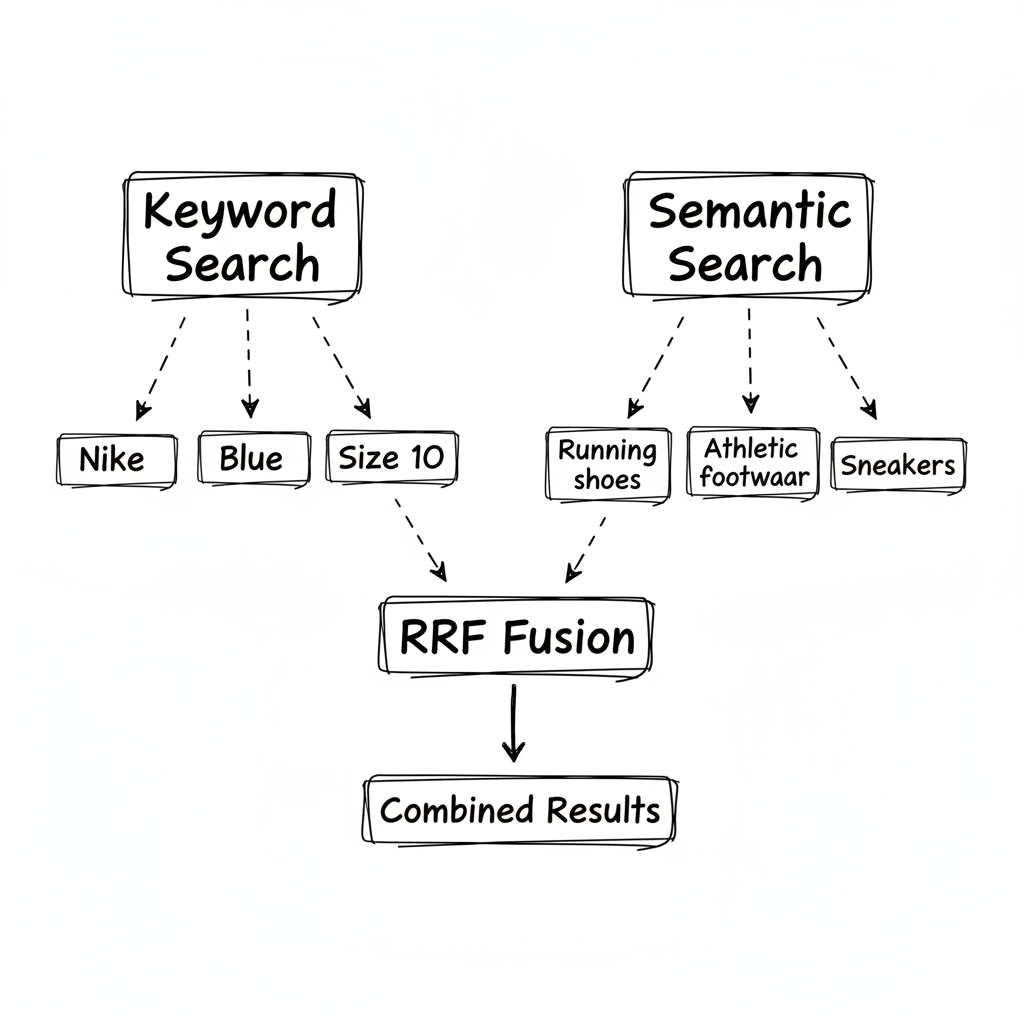

The user searched for "blue Nike running shoes size 10."

Our semantic search understood the intent perfectly. It returned running shoes. Athletic footwear. Performance sneakers. All highly relevant to the concept of "running shoes."

Just one problem: none of them were Nike. And none of them were blue. And size 10 wasn't anywhere in the filters.

I stared at the results, confused. The embedding model clearly understood "running shoes." But it had somehow decided that "Nike" and "Adidas" were close enough in meaning to be interchangeable. Which, semantically, they kind of are—both athletic brands. But that's not what the user wanted.

Meanwhile, our keyword search had the opposite problem. When someone searched "comfortable shoes for marathon training," it returned nothing. Nobody had written "marathon training" in their product descriptions. Keyword search was looking for exact matches that didn't exist.

Both search systems were working correctly. Both were failing our users.

The Trap: Picking One Approach

When we first added semantic search, the team had a debate: should we replace keyword search entirely, or run them separately?

We tried replacing keywords with vectors. Concept searches got better. Exact matches got worse. Product codes returned nothing. Brand-specific queries returned competitors.

We tried keeping them separate. "Use keyword search for SKUs, semantic for descriptions." This sounds reasonable until you realize: who decides which mode to use? The user doesn't know. And many queries are both—"blue Nike running shoes" is a keyword query (Nike, blue) AND a semantic query (running shoes).

"Different queries need different ranking signals, and you often can't tell which type you're dealing with."

The Insight: You Can't Add Scores, But You Can Compare Ranks

I was reading a paper on search fusion when I found the trick.

The problem with combining keyword and semantic search is that their scores are incompatible. Keyword search (BM25) might return scores from 0-20. Vector search (cosine similarity) returns scores from 0-1. You can't just add them—the scales are completely different and vary by query.

But here's what you can compare: rank positions.

If a document is ranked #1 in keyword results and #5 in semantic results, that means something. The document is highly relevant to the keywords AND moderately relevant to the meaning. Documents that appear in both lists are probably more relevant than documents that appear in only one.

The formula is called Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF): RRF_score = 1/(rank + k) where k is a constant (typically 60) that controls how much top positions dominate.

Documents relevant in multiple ways should rise above documents relevant in only one way.

The Implementation

Run both searches in parallel. Build rank maps for each. Compute RRF scores by combining the reciprocal ranks. Sort by final RRF score.

Now "blue Nike running shoes" works properly. The semantic search finds running shoes. The keyword search finds Nike and blue. Products that match both criteria—Nike running shoes that are blue—get boosted by appearing in both result sets.

What I Got Wrong Initially

I ran the searches sequentially. Big mistake. The two searches are independent—run them in parallel. Total latency should be max(keyword_latency, semantic_latency), not the sum.

I forgot about timeouts. What happens when one search times out? I added fallback logic: if semantic times out, return keyword results alone (with a quality flag). Degraded hybrid is better than no results.

I used the wrong k value. The constant k controls how much to trust top positions. k=20 makes top positions dominate. k=60 is balanced (the standard choice). k=100 is democratic—positions #1 and #5 have similar weight. I started with k=20 because I wanted exact matches to win. But that made results too narrow—users complained that they weren't seeing alternatives. k=60 worked better for our use case.

I didn't classify queries. Some queries are obviously keyword-only. Product codes. SKUs. Model numbers. Running semantic search on "SKU-12345" is wasted compute. I added query classification to skip unnecessary searches on 20% of queries without hurting relevance.

When NOT to Use This

- Latency is critical. Two searches take longer than one. If you need less than 10ms, pick one approach and optimize it.

- One signal always wins. If your domain is all product codes (no semantic ambiguity), keyword search alone is fine.

- Index is huge. Running two searches over billions of documents doubles compute cost. Consider whether the relevance gain is worth it.

- Search is already good enough. Hybrid adds complexity. If users aren't complaining, simpler is better.

The Takeaway

For months, I thought of keyword search and semantic search as competing approaches. You pick one. You optimize it. You accept its tradeoffs.

But they're not competing—they're complementary. Keyword search finds the exact terms. Semantic search finds the meaning. RRF combines them without needing to normalize scores, because it only looks at ranks.

"Blue Nike running shoes" now returns blue Nike running shoes. The semantic search finds products relevant to running. The keyword search finds products that are Nike and blue. Products that satisfy both criteria float to the top.

Neither search could do it alone. Together, they get it right.