The GPU ran out of memory at 3am. By the time I woke up, 10,000 items were stuck in a retry queue, and the processing pipeline had been frozen for six hours.

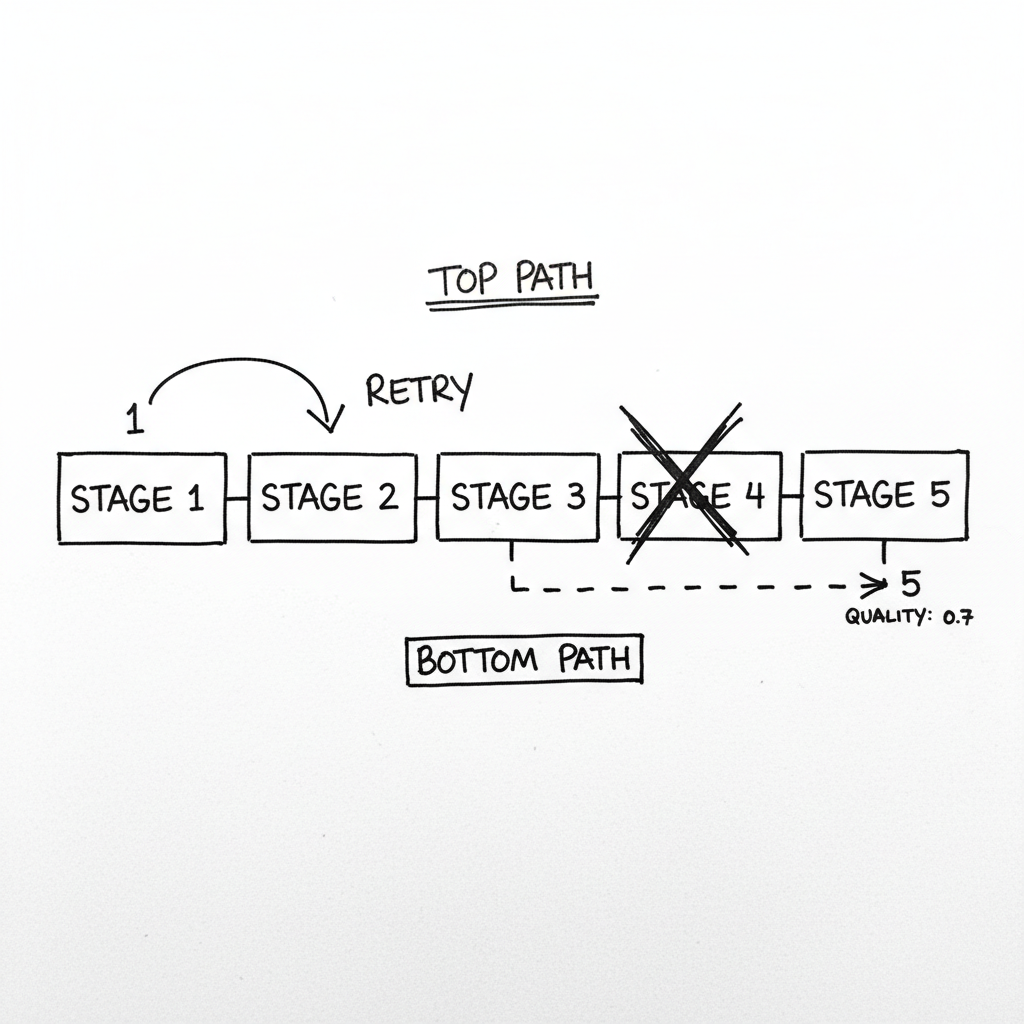

The frustrating part? Stages 1 through 3 had already completed for all of those items. They'd been fetched, validated, and partially enriched. But stage 4--the image classification step--had failed. And because my pipeline was built as a linear chain, a failure at stage 4 meant everything after it never ran.

I spent the morning draining the retry queue, watching items flow through one by one. And I kept thinking: most of these items didn't even need image classification. It was a nice-to-have. Why was I blocking everything on a nice-to-have?

The All-or-Nothing Trap

My original pipeline looked like this: fetch, validate, extract text, classify image, generate embedding, store. Clean. Simple. And completely wrong for production.

When stage 4 failed, I didn't just lose stage 4. I lost all the work from stages 1-3. Those items went into a retry queue where they'd start over from stage 1. Wasted compute. Wasted time.

Even worse: when stage 4 failed for many items (like during a GPU memory issue), the retry queue grew faster than I could drain it. The whole system ground to a halt.

The Realization

I was explaining the problem to someone, and they asked: "What happens if you just... skip stage 4?"

My first reaction was: "Then the data would be incomplete!"

But then I thought about it. Incomplete data is still data. A product without image classification can still be searched by name. A document without embedding can still be found by keyword. The classification made results better, but its absence didn't make them impossible.

"Partial success is not the same as failure. It's a valid state--as long as you track it."

The New Model: Fallback Chains

Instead of treating each stage as pass/fail, I gave each stage a fallback chain. Image classification could fall back to a CPU model (slower), then rule-based heuristics, then skip entirely with confidence zero.

Here's the key insight: every stage should have a "skip" option as the last fallback. Sometimes the right answer is "I don't know"--but saying that explicitly is better than blocking the whole pipeline.

Tracking Degradation

The tricky part: you can't just silently degrade. Downstream systems need to know what they're getting.

I added quality scores that decay as fallbacks are used. If classification (0.9 penalty) and embedding (0.8 penalty) both used fallbacks, the final quality score is 1.0 x 0.9 x 0.8 = 0.72.

Now downstream systems can make informed decisions. Search can rank high-quality items above low-quality ones. A dashboard can show the quality distribution. A retry queue can prioritize items with low quality for reprocessing when capacity returns.

The Difference Between Null States

This took me a while to get right. When a field is null, it could mean several things: not yet processed, failed, not applicable, or deliberately skipped.

These are very different states, and treating them all as "null" leads to debugging nightmares.

Now every stage result includes explicit status with the actual value, status indicator, error message if any, which fallback was used, and whether retry is possible.

What Bit Me in Production

Circuit breakers are essential. The first time the external API went down, my fallback logic kept hammering it. Every item tried the primary, failed, then used the fallback. That's a lot of failed requests. Now I use circuit breakers: if a stage fails N times in M minutes, skip straight to the fallback for a while.

Retry queues for low-quality items. Items that used fallbacks should be reprocessed when the primary path recovers. I queue any item with quality score less than 0.8 for eventual retry at LOW priority.

Some fallbacks are incompatible. If stage 3 uses fallback A, stage 5 might need fallback B to maintain consistency. I document these constraints explicitly and enforce them in the merge logic.

Test the fallback paths. This sounds obvious, but I'd only tested the happy path. When the GPU actually failed, I discovered my "CPU fallback" had never been run in production and had a subtle bug. Now I have a weekly test that forces fallback mode on a sample of items.

When NOT to Use This

- Correctness is mandatory. Financial calculations, safety systems--you can't serve "mostly right" data.

- Quality is your product. If users pay for high-quality results, degraded output damages your value proposition.

- Stages are tightly coupled. If stage 5 assumes stage 3 succeeded, you can't skip stage 3 without rewriting stage 5.

- Complexity budget is spent. Each fallback path is another thing to test and maintain. If you're already struggling with complexity, more paths won't help.

The Takeaway

For months, I treated my pipeline as a chain where every link had to hold. One break, and the whole chain failed. Items piled up in retry queues. Outages cascaded.

Now I think of it differently: each stage either succeeds, falls back, or skips--and every outcome is valid, just with different quality. The pipeline always moves forward. Items always get processed. The quality score tells you how much you can trust the result.

When the GPU fails at 3am now, I don't wake up to 10,000 stuck items. I wake up to 10,000 processed items with a quality score of 0.7. Not perfect. But processed. Searchable. Available.

That's the difference between a pipeline that runs in production and one that runs in theory.