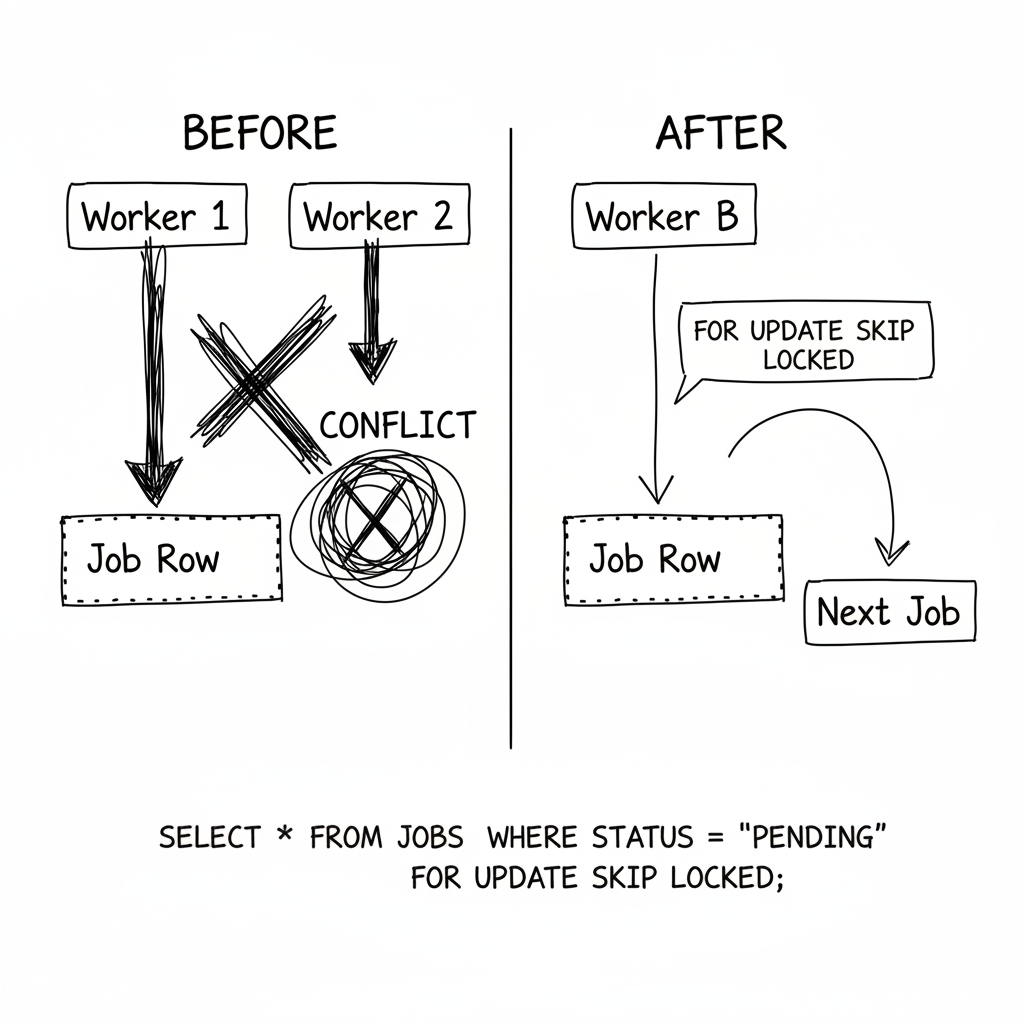

Two workers. One job. Both claimed it.

I watched the logs in disbelief. Worker A picked up job #4521. Worker B picked up job #4521. They both started processing. They both finished. Worker A's result got saved. Then Worker B's result overwrote it.

The data was corrupted--a weird hybrid of two different processing runs. And this wasn't a rare race condition. It was happening dozens of times per hour.

My first thought: "I need a distributed lock. Time to add Redis."

The Obvious Fix (And Why I Didn't Use It)

Distributed locks are the textbook answer. Before processing, acquire a lock. When done, release it. Redis makes this easy with SETNX. Redlock makes it "safe." Every tutorial points you there.

But I hesitated. I already had a database. Adding Redis meant: another service to deploy and monitor, another failure mode (what if Redis goes down?), lock expiration edge cases (what if processing takes longer than the TTL?), and extra network round-trips for every job.

I stared at my job queue table. It had a status column: pending, processing, completed, failed. The workers were selecting jobs where status equals 'pending', then updating them to 'processing'.

The problem was obvious: the SELECT and UPDATE were two separate operations. In between, another worker could grab the same job.

Then it clicked. What if they weren't separate?

The Trick: Make Selection and Locking Atomic

Instead of two operations (SELECT then UPDATE), I combined them into one atomic operation using FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED.

UPDATE jobs

SET status = 'processing', worker_id = 'worker-A', started_at = NOW()

WHERE id = (

SELECT id FROM jobs

WHERE status = 'pending'

ORDER BY priority, created_at

LIMIT 1

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

)

RETURNING *

The magic is in FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED. It means: "Lock the row I'm selecting, but if it's already locked by someone else, skip it and find another one."

Now when two workers race for the same job: Worker A's UPDATE succeeds, returns the job. Worker B's subquery skips the locked row, finds the next pending job instead.

No Redis. No distributed locks. Just SQL doing what SQL does well.

What I Got Wrong Initially

I forgot about crashed workers. If a worker grabs a job and then dies, the job stays 'processing' forever. Nobody else will pick it up.

I added a cleanup query that runs every few minutes to reset jobs stuck in 'processing' for over 30 minutes back to 'pending'.

I didn't track attempts. When a job fails and gets retried, I need to know how many times it's failed. Otherwise, broken jobs retry forever. Now I increment an attempts counter and only pick up jobs below max_attempts.

I made the timeout too short. Some jobs legitimately take 25 minutes. My 30-minute timeout was resetting them while they were still running. Now I track last_heartbeat and have workers update it periodically. The cleanup query checks heartbeat, not start time.

The Pattern Generalized

The core insight: you can use conditional UPDATE as an optimistic lock. The UPDATE only succeeds if the condition is still true.

"Every UPDATE is already atomic. Every WHERE clause is already a condition. I just needed to combine them into a single statement."

For claiming work: update status to 'processing' where the job is still pending, using FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED. For completing work: update status to 'completed' where the job is still 'processing'. For failing work: update status based on attempt count--back to 'pending' if below max attempts, otherwise 'failed'.

When NOT to Use This

- Cross-database coordination. If the lock and the work are in different databases, you need actual distributed coordination.

- Sub-millisecond latency requirements. Database round-trips add latency. For high-frequency trading, you want in-memory locks.

- Complex lock hierarchies. If you need to lock multiple resources in a specific order, SQL gets awkward. A proper lock manager helps.

- When you already have Redis. If Redis is already in your stack and you're comfortable with it, Redlock is fine. Don't avoid it just to avoid dependencies.

The Takeaway

For months, I assumed job queue coordination required a dedicated locking service. Redis, ZooKeeper, etcd--pick your poison.

But my database was already coordinating transactions. Every UPDATE is already atomic. Every WHERE clause is already a condition. I just needed to combine them into a single statement.

Two workers still race for the same job sometimes. But now only one wins. The other moves on to the next job. No Redis. No extra infrastructure. Just SQL doing what it's always done.